Down and Out in Belgium

Down and Out in Belgium

By W. Budd Wentz, MD, CAPT USAAF

with Tom McCrary

On Station in England

It was the first mission for my crew and almost the last mission for all of us. The nine of us arrived at Eighth Air Force Station 137 in Lavenham, England in late 1944. We sailed from New York City to England aboard the Queen Elizabeth. Crossing the North Atlantic in winter was cold but happily uneventful. When we pulled up to the airbase I was startled to see dozens of B-17 Flying Fortresses parked off in the distance. I asked the Captain who met us what were those bombers? We were a B-24 Liberator aircrew! After several moments of disbelief, the Captain resigned himself that the Bomb Group would have to accept us as we were and get us checked out quickly on B-17s. The war was taking it’s toll on the 8th Air Force and the 487th Bomb Group (Heavy) desperately needed replacement crews. For several days we had a chance to become acquainted with the B-17.

There was a policy in the 487th that the first pilot of a replacement crew fly his first mission as a copilot with an experienced crew. Then the replacement pilot would have one combat mission experience before he took his crew out on their initial mission. My first mission was Operation Thunderclap flown on 3 February 1945 as a maximum effort involving 1,437 four-engine B-17s and B-24s and 948 fighter escorts to Berlin. There were planes as far as I could see – stretching to the horizon in every direction. It was like a sky full of black dots.

Take Off

Several days later my crew and I prepared for our 1st combat mission together with the 838th Squadron. From the morning briefing this trip was expected be uneventful for our crew. I had learned a lot on my first mission but soon would be forced to realize that there was so much more to learn. That morning the skies were clear and the mission was on. We were headed to Weimar, Germany.

We took off east to west on runway 1 at about 0900 from Lavenham in B-17G-75-BO #43-38033. Some aircrews named the main runaway “The Bathtub” because of the “big bow” in it. Trying to get the fully loaded fortress off the ground, going up hill, could be a struggle. I would sit at the very end of the runway with my brakes on and increase throttle to full power before starting to move. Once airborne we began our escalation and climbed to 16,000 feet. It was easy to identify our group formation with the large boxed [P] on the B-17’s huge yellow tails and slide into our assigned No.11 position in the squadron. Ours was the last plane of a formation of 3 Vee’s of nine planes in tandem. The position was called “Tail End Charlie” and was almost always assigned to the newest in the group. It was the most difficult position to fly due to the constant jockeying around to stay in formation. This was also the most dangerous spot because it was more vulnerable to German fighters.

Take off East-West from Station 137

Channel Crossing

As we crossed the Channel and reached the coast of France, the group entered a solid bank of dark clouds. Now we were flying in close formation inside dense clouds with poor visibility. The lead plane took the group to a higher altitude but the clouds extended even higher so we returned to our planned altitude. Instrument flying isn’t dangerous once you learn to use and trust the instruments. But flying in close conditions relying on instruments can be fatal. The pilot must constantly keep jockeying to stay in his assigned position while letting the co-pilot watch the instruments. The formation’s lead plane flew on automatic pilot and course adjustments are made by very slight changes. It can be very tedious and tiring.

Hit Over Germany

The formation continued flying eastward into Germany on our way to Weimar. By monitoring the group radio channel we learned the forward planes had crossed the border into Germany. We started hearing reports of accurate anti-aircraft fire from the German radar-directed guns. Minutes later we heard several metallic noises and felt the plane shudder as we were hit by German flak. The No.4 engine started losing power and causing drag. I feathered the engine so the edge of the propeller blades faced forward to reduce the drag. We could not keep up with the formation, so I banked left to head back west towards the French coast. To keep airborne we jettisoned our armed bombs through the clouds. We don’t know what was hit, but knew it was within German borders. As we continued westward we suddenly lost power in the No.3 engine, so I feathered it as well. Now only two of the four engines remained. Although the B-17 can still fly on two engines we needed to reduce altitude and reduce weight to keep up our airspeed. We continued to let down slowly and had the crew toss overboard anything possible to reduce the load, including ammunition from the 10 machine guns.

Distinguished Flying Cross Citation - "Just after the bombs were released on the target, Lieutenant Wentz’ plane was struck by flak which rendered two engines inoperational. Although another engine lost power while they still were over enemy territory, he skillfully flew the bomber safely out of enemy territory. When his fourth engine stopped functioning, he ordered the crew to bail out. Checking before he jumped, he discovered that the gunners in the waist of the plane had been trapped. He courageously returned to the controls of the plane and successfully crash-landed the bomber without injury to any of the crew members on board."

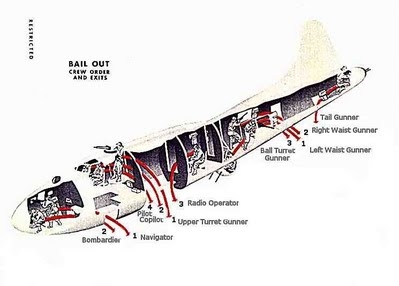

Boyer (Navigator) worked feverishly to plot our position as I struggled to keep the same westward compass heading. Hidden in the clouds we felt fairly safe from Luftwaffe fighters. Being alone over enemy territory was a dangerous situation for a bomber. We continued westward slowly losing speed and altitude along the way. About 15 minutes later and at 3,000 feet the No.1 engine heated up and began losing power. We must have been hit by flak all over. It was not possible to remain airborne much longer, much less to make it back to England. It was time to bailout, regardless of where we were. I called out over the inter-phone and rang the bell to order the crew to bailout. The 4 crew members in the front of the plane (Navigator, Nose Gunner, Engineer, Co-Pilot) parachuted out as I held the plane level. Again I rang the bell and called out to the crew in the rear to get out. Just then the No.2 engine seized up. The 4 crew members in the rear still had not responded. I could not bail out since the 4 rear crew members had not yet escaped. The wounded plane had to be landed one way or another.

The bomber was losing altitude rapidly and the last engine died as I finally came out of the clouds. I had less than 500 feet to prepare for a crash landing. Off to the left I could see a fairly flat field and started aiming for it. While keeping the plane somewhat level I turned off all the switches within reach. At the last second I raised the nose slightly so I wouldn’t plow nose first into the field and flip end over end. Although the controls were sluggish, luckily the plane still responded. I hit the ground hard, bounced once, plowed into the mud, and eventually stopped at the edge of a lake. Anxious about fire, I got out of my seat as quickly as I could and headed for the rear of the plane. Entering the fuselage I saw the bomb-bay doors had broken away. To my surprise, there were the remaining 4 rear crew members half buried in mud that came through the bomb bay doors while landing. We all helped each other scramble out in case the plane caught fire. There was no more ammunition or bombs on board but lots of fuel still remained in the tanks. Fortunately I had turned off the master switches so the electric circuits weren’t shorting out and causing sparks.

Emergency Landing near Rienne

Five of us stood dazed outside the silent plane and commented on our good luck. Everyone was shaken, yet unharmed. Not taking too much time to revel in our safe landing, we started scanning the surrounding area. A tiny village was just to the north about 300 yards away with about a dozen houses and a church. I was surprised to see the little village since there wasn’t much time after coming out of the clouds; I was too busy aiming toward the field, letting down the flaps and tuning off the switches to notice anything on the right side of the plane. Suddenly we spotted a group of about 50 people running from the village towards the plane. The five of us, Carson (Radio & Waist Gunner), Jewell (Tail Gunner), Barczy (Waist Gunner), Robins (Belly Gunner), and I (Pilot), were standing by the plane. They hadn’t spotted us yet since we were on the opposite side of the plane from them. Running to the rear and peering around the tail we could see that they were all dressed in civilian clothes, not military uniforms. I thought of all the petrol in the tanks since we didn’t use very much. There still was a real possibility of fire. So I took my chances and began yelling at the crowd to stop and stay back. My shouting in English was ignored and my knowledge of French was poor. Suspecting we were in Germany, it didn’t seem very prudent to try French. We could have been in France, Belgium, or Germany. I began shouting in German “Stop! Fire!”, “Halt! Feuer!”. Suddenly the atmosphere of the crowd changed to growling and shaking their fists with nasty looks. I switched back to English and began yelling “American, United States,” but to no avail. Either they did not understand or they did not speak German.

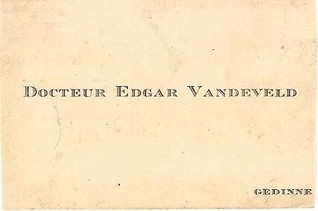

A small truck appeared on the scene and five rough looking men came running over with rifles and sub-machine guns. I attempted to explain that we were Americans, which also appeared to be unsuccessful. The five men muttered to themselves and looked angry. At this time a Mercedes convertible car bumped across the field. A well dressed man about 45 years old got out of the car and walked over to the five armed men. The way the men reacted suggested he was the leader of the group. After conversing with the men, he turned and looked at me and my crew and the plane. We were all wearing flying clothes. I had no hat, no insignia and wore a dark green parka with a hood, light brown flying suit and Eskimo-like mukluk boots. My other crew members had leather helmets and electric flying suits over their clothes and fur-lined leather boots. Inside the pant legs of our flying suits we all carried curved individual escape kits. Even though our plane had American markings and no German swastika markings, the villagers and armed men could have thought we were German. There had been reports that downed Allied planes had been recovered by the Luftwaffe, repaired and flown in disguise in American and British formations. However the well dressed man seemed ready to believe us. I suspect that the B-17 sitting in the mud with a big USA roundel star insignia on the side was far more convincing than my crew or my shouts. Fortunately, he spoke English. After the head man calmed the people down we spoke for a few minutes and he revealed that he was Doctor Edgar Vandeveld, a physician from the somewhat larger, village of Gedinne, about 2 miles east. Edgar was the head of the underground resistance unit for the area.

Rienne Maquis from Jean Nicolas, 1945

Friendlies Hide Crew

We were in Belgium, about 7-10 km from the French border, near the village of Rienne on Lake Boiron. (Rienne is about 230 miles from Lavenham.) Although there were no German troops quartered in the village, trucks with German soldiers would drive into the village at odd hours and stay for 15 to 20 minutes, 3 or 4 times a day. Later, we learned that Edgar had given orders to all the local people to tell the same story to the Germans about seeing a B-17 close by in the pasture. They were to say that nine people immediately left the airplane and were seen walking across the field in a south-easterly direction toward the French border. Edgar was quite confident that there were no traitors in the village, a fact later confirmed by the local Priest.

A small truck, driven by one of the doctor’s group, drove up with our missing four crew members who had parachuted. With the exception of Hanford (Nose Gunner), who had fractured his ankle, they were also unharmed. Hanford landed on a railroad track in the middle of Gedinne. Dr. Vandeveld treated him by setting his ankle in a cast. Time was pressing on us and we were anxious to depart the area before any Germans arrived. But before we left the Maquis asked if they could have the gas from the plane. By now it seemed fairly safe that the plane wasn’t going to blow-up or catch fire, so we acted quickly and I took my pilot relief tube and motioned that it could be used to siphon out the gas. The first siphon was not gas. After spilling out and making faces, the Belgian was able to get a stream of gas flowing through the tube into the truck.

Reinne 2003

The doctor took all nine of us to a small bistro in Rienne where we had several cognacs to celebrate our good fortune. After the refreshments, the Doctor proposed we divide up the crew into three groups and each trio stay in a different house. He did not want to lose his small supply of gas using the two resistance group’s trucks to take us to Brussels. The Battle of the Bulge was winding down and the American infantry was expected to be moving east and pass though Rienne soon. Rienne is located less than 40 miles southwest of Bastogne.

I was quite aware of the scarcity of food for civilians in German occupied territory and remembered that we had two sealed cases of food stored in our plane. After it was dark, Boyer (Navigator) and I went back to the crash site to get the food as well as the Norden bombsite to prevent the Germans from getting either. I took the clock as a souvenir of our fateful event. Returning to the Bistro we opened the two cases of food and emptied out the contents to divide into three piles for the three groups. The cases contained cans of roast beef, cheese, vegetables, rice, candy, fruit, cigarettes, aspirin, matches, coffee, powdered milk and sugar. A woman who lived in the house above the bistro volunteered to take in one group of airmen. Women from two other families in the village were also quite willing to help and hide the other two groups of US airmen. Each woman was given a third of the food to augment her family’s meager diet and share it with her 3 unexpected “guests.” I instructed the crew members to stay indoors and away from the windows. It now seemed that we were fairly safe and hoped that the American troops would arrive soon. For security reasons we were not told where the other six crew members were hidden.

Now that the situation had calmed down and we were safe for the moment, we pondered the potential fate of the three families who took us into their homes. I knew that the penalty for hiding enemy soldiers was execution. I was worried that if the Germans did not believe the tale of us walking to France they would began searching the houses. If that happened, we were all to run out the back doors and into the woods behind the houses. That way the Germans could not prove which house quartered any of the crew. Perhaps this late in the war the villagers wouldn’t be so brutally punished if we were captured. I hid in the house above the local bistro. The owner had been a resistance member and the mayor of Rienne. He had been taken to a concentration camp and died there. His wife acted as mayor for the duration of the war and was also involved in the Underground Resistance. She did not seem as concerned as I was about being found by the Germans. She had a son about 11 or 12 years old that I gave my binoculars to as a remembrance.

Communicating with Allies

The next day I wanted to get a message back to England to inform our unit that we were all still alive. Doctor Vandeveld thought that this was possible. It was important to me to keep our names off the Missing in Action Report (MACR) to prevent our families from hearing that we were missing or dead. Around 11:00 pm that night, the Doctor and a few others came for me in their truck. We rode about 7-8 miles up a small mountain to a tiny cabin hidden in the woods. Several times while driving we had to get out of the truck to remove logs that had been placed across the road. Once we arrived at the cabin the Doctor contacted an agency in England by radio. With instructions to keep my communications short and say a little as necessary, I reported my name, rank, serial number, air force base number, and that the entire crew was alive and well. The Doctor was pleased with the briefness of my message. I felt better afterward. Later I would learn that the MIA and MACR reports did not in fact include us. What a relief for our families!

Thankfully, our time in hiding was safe and restful to the point of being tedious. We could neither go outside nor could we communicate with the villagers in any serious manner, since none of us could speak French or Walloon. We had no money. Frequently, I cautioned the crew to go sparingly on the villagers’ wine and cognac.

Americans Arrive

The next morning around 9:00 am we heard noises in the street and I peeked out the window. Outside were four or five American soldiers in front of a Jeep walking up the main road in the village. I ran out into the middle of the road to flag them down. As they approached, I said “Where in the hell have you been? We’ve been waiting for you”. The three men did not enjoy my greeting and responded with numerous four-letter words. The Captain in the jeep stopped and came up to me. I quietly pointed to the downed B-17 off in the field resting low in the mud with the bent and twisted propellers. The grumpy Americans seemed mollified by my concise and visual account. There was little they could do, and they needed to push on with the march. The Captain wasn’t able to supply us with food, but promised to get on the radio and have a suitable truck come back for us when possible. Now that we knew we were safe, it was possible to come out of the homes, walk around, and thank the people. I learned the Priest was key in getting the villagers to cooperate and take us in. We decided to go back to the plane and see what else could be salvaged. We located the life-raft unscathed in the plane and blissfully floated around the small lake for a while. Given that I felt we were safe, I took the flare pistol and shot off the whole carton of red and green flares for the local inhabitants. Everyone had reason to celebrate for they were now behind friendly lines.

To Brussels

The next morning after the Americans passed through Rienne a large green military truck with benches along the sides and a canvas cover came to recover us. We said our adieus and thanked the Belgian families and Doctor Vandeveld for all their help and sacrifice. Doctor Vandeveld came over when he heard we would be leaving. He gave me his card and wished us luck. It was a long cold ride northward through Givent and Namur to the outskirts of Brussels about 140km away. We finally stopped in front of a large two-story building surrounded by a high stone wall. It was a convent. Here is where we were to stay until we departed Brussels.

The Mother Superior, as she would be called in the United States, greeted us in a grim fashion reminding us of where we were. After a meager meal of soup, bread, and tea, each airman was assigned a small sparse room with a narrow bed and little more. We were told to stay in our room until breakfast the next morning. After breakfast of tea and bread, another large truck with English markings picked us up. The truck was driven by a senior British sergeant who took us to an office at a large airfield occupied by the Royal Air Force. Undoubtedly it had had been a Luftwaffe fighter base. I told them we were in a hurry to get back to our own base in England and that we had been wearing the same clothes for the last 5-6 days. The British officers were not impressed and refused to put us on a transport plane headed for England. Several American C-47s with British markings were sitting there with the engines turning over. I reminded them that they were American planes and I knew they were going to England. As you might expect, they seemed to take umbrage at my remarks and I was reminded of how little respect and influence is awarded to 20 year old lieutenants! We were given some Occupation Script to spend, told to have a good day, not to get into trouble, be back to the convent before 9:00 pm or we would sleep on the street, and were sent on our way.

On the second morning in Brussels the truck picked us up again and we repeated the same events as the day before. We spent two days walking around the city and visiting two museums which had just reopened. After another frugal day we decided to go to a good restaurant for a change. A policeman pointed out a very fine restaurant, but we were hardly dressed suitably in our flying clothes. He reckoned we might not be served. Nonetheless, head strong and feeling due, we went ahead anyway. The three others decided to eat at a small bistro close by. A rather formal maître d’ looked pained when we requested a table for six. I explained that we would have worn better clothing but we left our best suits in England. Reluctantly, he took us to a table in the corner of the room. The wine was superb! The food was fair, but well prepared, and violin music was excellent. He took all our money.

The most remarkable sight was several tables of well-fed, prosperous-looking, middle-aged couples enjoying the evening with a number of waiters scurrying around and serving them. It seemed odd after four years of war, under German and then British occupations, that some people could escape the hardships of war. I asked our waiter if these people came in frequently during the German occupation and he assured me that they had. I realized that for the privileged few, a world-wide war was only a minor annoyance and life went on as usual.

The next morning, we went again to the RAF airfield in Brussels and were finally told there would be room for us on one of the military transports. We were elated at the prospect of getting back to our base. Since this was Friday, it was interesting to note how many highly-ranked and well dressed British officers were headed to London carrying only a briefcase. Many frowned when they noted nine unimpressive, disheveled-looking men in the back who were not wearing proper uniforms.

Near London

It was dark, cold and snowing, when we landed at some field near London. The people in front filed out, and I lead the group to the door and down the metal steps. At the base of the stairs two sergeants and a captain yelled at us to get back in the plane and sit down. The three men followed us into the plane with their weapons drawn and ready. This situation had not been covered in our Flight Training! I didn’t like the way they held their guns at us. I asked what the hell was going on and that we were anxious to get back to our base. The captain, who was not the most impressive officer I had ever met, informed me that he was S-2 Intelligence, and that we were not going anywhere until he was convinced that we were not Germans trying to sneak into England. It had happened in the past.

After the usual questions of name, rank, serial number, bomb group, and location, he began to question me about baseball. Since I had very little interest and knowledge of professional baseball, I was not able to answer his questions. I told him that I was not fascinated by baseball and did not know which teams were in which leagues. He seemed to get disturbed by this and kept repeating the questions louder and louder. At a pause, another officer asked where I was born. I responded, “Philadelphia.” He asked if I had grown up in the area. When I said, “Yes,” he asked a number of questions about the city: stores, addresses and schools, which I could answer. This seemed to finally satisfy them. The manner in which I responded as well as the language I used certainly would not have been used by Germans looking to be accepted.

Back to Lavenham

We were led to another large canvas-covered truck and made the two-hour trip back to our airfield. In Lavenham, I persuaded the driver to go to the mess hall where he could warm up and have a hamburger and french fries with us before he drove back. After eating, the nine of us made the short walk back to our Neissen-huts and our friends. Fortunately, the radio call I made from Belgium had been reported to our group. Our clothing and equipment was still as we left it and we weren’t listed as missing-in-action. Going to headquarters to report back that night could wait. Instead a shower and sleep was in order.

After breakfast that morning I headed over to headquarters and reported in. I reported the final details of our experience when I saw the Commanding Officer of the 487th BG, Col. William K. Martin. He said he was glad to see us back, appreciated the message so that we would not be MIA. If I had already flown six or more missions, we would have been grounded and sent back to the States. Since he was so short on crews we would have to fulfill the entire thirty-five mission quota. And so our first mission and evasive adventure was over. Welcome back to the war, boys. Another day in Lavenham started again.

Little did we know or expect that fate would step in again during our tour of duty and we would never complete the required 35 bombing-missions to Germany. This was the first of five emergency landings we made in the next two months. Sixty-one years later, I found that we were eligible and I became a member of the Air Force Escape and Evasion Society. Dr. Edgar Vandeveld was our Helper.

Distinguished Flying Cross

On 23 April 1945 I was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross. “For heroism and extra-ordinary achievement while serving as pilot of a B-17 aircraft on a combat mission over Weimar, Germany, 9 February 1945. His actions on this occasion reflect the highest credit upon himself and the Army Air Forces.”

Reinne 1989

History of B-17 #43-38033

1944/06/17 Delivered Cheyenne 1944/06/28 Kearny 1944/07/11 Dow Fd Assigned 834 BS / 487 BG [2C-G] 1944/07/05 Lavenham 1945/02/09 b/d Weimar f/l Riennes,Be 1945/03/13 Salvaged 52.666667°, 9.833333° Source: "THE B-17 FLYING FORTRESS STORY" by Roger A. Freeman

September 20, 2018 at 9:24 pm

Awesome story. I wished my Grandfather’s name was spelt right lol. But amazing story none the less 🙂

LikeLike

September 21, 2018 at 3:51 pm

Fixed misspelling. Thanks for the comment.

LikeLike